Space Swoon: NASA drops image of Venus that reveals nightglow on the planet’s edge. Well done, fellas!

Ey! Yo! Take this glorious image of Venus and the nightglow on the planet’s edge to the dome! It’s a Tuesday! That fucking sucks! But you know what doesn’t suck? Space!

Hit the jump to check it out, and gleam some details!

The Next Web:

The Parker Solar Probe, designed for detailed study of the Sun, has another advantage — it is able to examine planets as it passes their orbits. As it refines its orbit around our Sun, Parker will pass Venus a total of seven times over its seven-year mission. The Parker probe uses the gravitational pull of planets to bend its path through the Solar System.

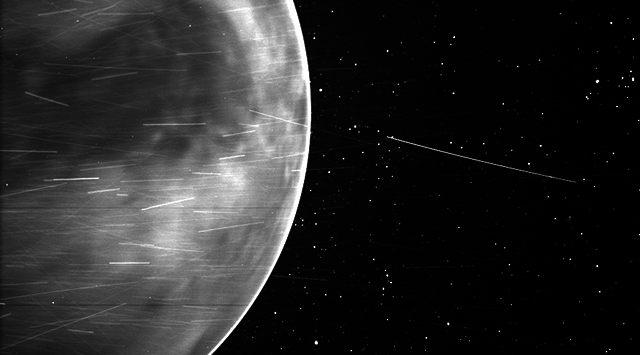

Recorded on July 11, 2020, a fascinating new image of Venus was taken during the third of Parker’s seven planned encounters with the Sun. This photo was recorded by the Wide-field Imager for Parker Solar Probe (WISPR) from a distance of 12,380 kilometers (7,693 miles) from the nightside of the planet.

“WISPR uses two cameras with radiation-hardened Active Pixel Sensor CMOS detectors. These detectors are used in place of traditional CCDs because they are lighter and use less power. They are also less susceptible to effects of radiation damage from cosmic rays and other high-energy particles, which are a big concern close to the Sun.

The camera’s lenses are made of a radiation hard BK7, a common type of glass used for space telescopes, which is also sufficiently hardened against the impacts of dust,” NASA describes.

This new image of Venus shows a bright ring bordering the edge of the planet. Researchers believe this might be nightglow — light emitted as atoms of oxygen, broken apart by sunlight, recombine into molecules.

“Sorry… my mind was wandering… one time it went all the way to Venus and ordered a meal I couldn’t pay for.” ― Steven Wright

The dark region near the center of the image is Aphrodite Terra, the largest highland region on the Venusian surface. This geological feature appears dark due to the fact that it is around 30 degrees Celsius (85 F.) cooler than the surrounding terrain.

“WISPR is tailored and tested for visible light observations. We expected to see clouds, but the camera peered right through to the surface,” explained Angelos Vourlidas, WISPR project scientist from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL).

This was a bit of a surprise to researchers, who did not expect WISPR to see ground features on Venus so clearly.

This presents a fascinating question for mission engineers and astronomers — why was WISPR able to see so clearly through the clouds of Venus? The two most-likely possibilities are either WISPR is able to see better in infrared wavelengths than designers believed, or there is, or was, a thinner region of clouds, allowing the camera to see through the haze.

Either cause offers exciting new science. If WISPR is able to effectively image infrared wavelengths of light, then we have a new tool to study dust and pebbles like that which formed the rocky planets of the inner solar system. If there was a previously-unknown break in the clouds, this feature could help us better understand the Venusian atmosphere.