Astronomers have just detected dozen of missing galaxies from the Early Universe. The Cosmos always excites, my dudes

I say, goddamn! Another week, another fantastic-ass find by astronomers. This time? Oh, they’ve just detected dozens of galaxies from the early universe. Previously hidden.

Gizmodo:

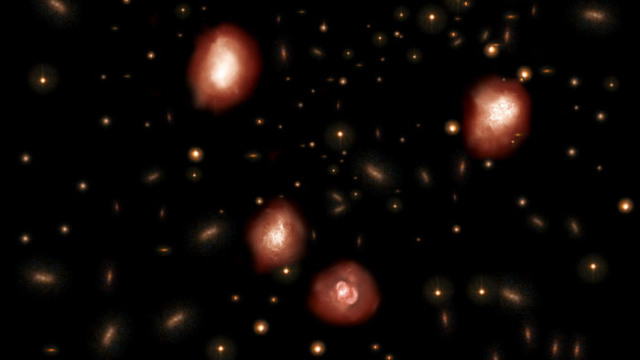

Astronomers have spotted a puzzling population of enormous galaxies in the far distance that will be crucial targets for upcoming telescopes.

Today, astronomers struggle to explain the origin of the largest galaxies in the nearby universe. This new discovery, made using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, offers an explanation—but something’s off. The newfound galaxies go against present-day models of galaxy formation. The discovery is a big deal for scientists studying galactic evolution.

“As an observer, nothing can compare with finding something new,” Tao Wang, the study’s first author from the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Tokyo, told Gizmodo in an email. “I am always intrigued by the largest galaxies (also supermassive blackholes and galaxy clusters) in our universe, and have been studying their formation and evolution since my PhD. Seeing that we have detected these invisible galaxies in the submillimeter wavelength with ALMA is one of my best memories in my life.”

Previously, scientists’ knowledge of the most distant (and therefore oldest) galaxies have come from their ultraviolet light, stretched into lower-wavelength infrared light by the expanding universe and imaged by telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope. But this technique requires that the galaxies actually emit ultraviolet light, that the light can escape the galaxies, and that the light isn’t absorbed by intervening dust. Scientists already knew this observational method underestimates the number of massive galaxies they see, and biases discoveries toward the most extreme star-forming galaxies, according to the paper published in Nature.

The researchers identified 63 sources of infrared light that appeared in the Spitzer Space Telescope’s infrared light camera but had too long a wavelength for Hubble to detect. They then followed up with ALMA, which is also sensitive to these far-infrared wavelengths, and confirmed 39 of these massive galaxies existing at an epoch around 2 billion years (or less) after the Big Bang.

These galaxies are important, explained Wang, because scientists previously couldn’t find candidates for the progenitors of the most massive present-day galaxies. “Our discovery has helped to answer these questions, providing evidence that the progenitors of the most massive galaxies in the universe are mostly dusty and remain hidden from optical light,” he said.

But new questions have taken the place of the old. Current models can’t explain how these potential massive galaxy progenitors formed so quickly, Debra Elmegreen, a Vassar astronomy professor not involved in the study, told Gizmodo. “Where are they? This paper finds them. But why are they there, then? We don’t know,” she said.

During the earliest era of the universe, scientists think that mysterious stuff called dark matter began clumping first, creating the universe’s web-shaped scaffolding. Electromagnetic radiation separated from matter, and matter began clumping in the filaments and nodes of that web. Galaxies started to form from this accumulated matter and grew either by absorbing gas from the web or by colliding with each other. But Elmegreen compared that growth to a drip, and the discovery of these ancient massive galaxies is like leaving a faucet dripping and returning just a bit later to see the bathtub had filled up. Scientists just didn’t think that such large galaxies could have formed so quickly, based on their understanding of how galaxies grow.

This discovery doesn’t include much in the way of spectroscopy, the specific wavelengths of light that allow scientists to determine a source’s composition, and there remain questions as to their exact age, explained Wang. The discovery leaves astronomers with a lot of exciting work to do.

“The next 10 to 20 years will consist of trying to understand these galaxies, and piecing together how the first galaxies formed and what they were made of,” Joaquin Vieira, associate professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who reviewed the paper, told Gizmodo.

This paper marks a timely discovery. The James Webb Space Telescope is scheduled to launch in 2021 and is sensitive to these infrared wavelengths, which will make it a useful tool for understanding these early massive galaxies.

“The bottom line is that when we have bigger toys with greater light-collecting ability and greater resolution, we can discover more things,” Elmegreen told Gizmodo. “This is opening up the next window.”