Dinosaur Tail Found Preserved in Amber And Covered In Feathers

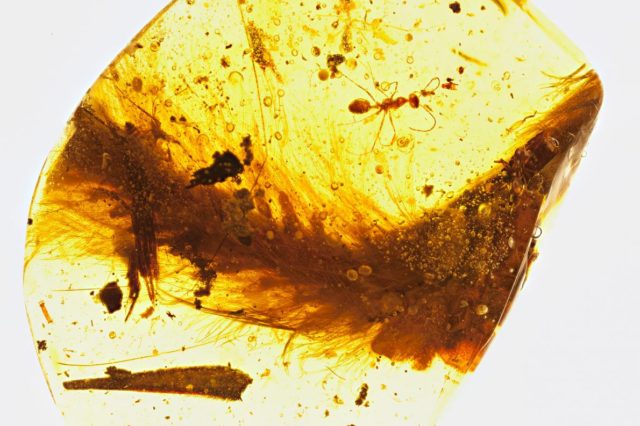

A dinosaur tail has been found! Preserved in amber. Covered in feathers. 99 million years old. Friggin’ rad.

Scientists have discovered a dinosaur tail with its feathers still intact trapped inside a piece of amber. It’s absolutely incredible.

These aren’t the first feathers to be found encased in amber, but they’re in such pristine condition that scientists can say they most definitely come from a dinosaur and not some kind of prehistoric bird. These feathers could very well be the first non-avian (i.e. non-bird) dino fragments found preserved in amber. This discovery, the details of which now appear in the journal Current Biology, is shedding new light on the finer details of dino feathers and how they evolved—details that can’t be inferred from conventional fossils alone.

Incredibly, the lead author of the new study, Lida Xing from the China University of Geosciences in Beijing, found the remarkable specimen at a market in Myanmar last year. The people selling the chunk of amber figured it contained some kind of plant matter, and that it would make for a nice piece of jewelry or a cool curiosity piece. Xing immediately recognized its scientific potential and recruited Ryan McKellar of the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada to aid in the analysis.

Using a CT scanner and a microscope, the researchers were able to analyze the amber piece in detail. They say the feathered tail belongs to a young coelurosaur, a family of bird-like carnivorous dinosaurs that lived during the Cretaceous era about 99 million years ago.“The [amber] material preserves a tail consisting of eight vertebrae from a juvenile; these are surrounded by feathers that are preserved in 3D and with microscopic detail,” noted McKellar in a statement.

Analysis shows that the upper surface of the tail was colored a chestnut-brown, and the underside a pale white. The feathers’ structure lacked a well-developed central shaft, or rachis, a feature found in modern bird feathers. But the feathers did have barbs and barbules—a pattern of branching found in modern feathers—suggesting that this feature arose quite early in the evolution of feathers.The researchers are hoping to find more such artifacts in the future. “Amber pieces preserve tiny snapshots of ancient ecosystems, but they record microscopic details, three-dimensional arrangements, and…tissues that are difficult to study in other settings,” noted McKellar. “This is a new source of information that is worth researching with intensity and protecting as a fossil resource.”