The Tree of Life Works Wonders

Coming to theaters during a summer overstuffed with sequels to big movie franchises, reboots to past successes with built-in fanbases, and potential blockbusters based on pre-existing properties from other media, Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life is nothing less than a godsend for movie lovers. A work of sheer originality and cinematic virtuosity, it attempts to inspect all of existence and humanity’s place within the awe-inspiring cosmos–and brilliantly boils it all down into one immensely perceptive family drama.

Malick triumphs in a way that only he can. The legendary and enigmatic director (of Badlands, Days of Heaven, The Thin Red Line, and The New World) succeeds by recognizing that existence is less about storylines and more about sensations, less about narrative and more about contemplative narrators. Using the most identifiable tools in his director’s kit–whispering and prayer-like voiceovers and some of the most gorgeous visuals involving the interaction between man and nature ever captured (thanks to the great Emmanuel Lubezki)–Malick fashions a film that is entirely its own, but also manages to get at humanity’s universal exploration for meaning and peace, by using all that we have: our consciousness. The voiceovers are offered up to the heavens, in the hope that someone or something is out there listening, while a floating and fluid camera follows in and out of thoughts and memories, ever-searching, allowing for audacious transitions from image to image, scene to scene (if they can even be called “scenes”). Chronicling the inner workings of the characters’ psyches, piercing each overwhelming emotion or newfound dilemma (both spiritual and corporal), the voiceovers and camerawork provide the necessary thrusts into spellbinding territories and perfectly capture the stream-of-consciousness of the roaming mind of man.

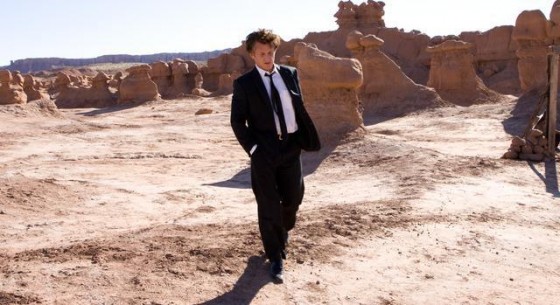

Here, that man is Jack (Sean Penn), a man in the middle of his life, caught between the formative past and the looming future, wrestling with all the demons and existential angst of the present. Still grappling with the fruits of his upbringing and the death of his younger brother, detached from the woman with whom he shares his bed (and apparently little else), and unsatisfied with his job as an architect inside a high-rise complex of oppressive mass (that both bears down on him and weeds out most beautiful greenery and blue skies), Jack wants to know how he got there, to the point where he wants to know how everything got to be the way it is up until he gets there. Or, more schematically speaking (After all, he is an architect.), Jack wants to know how he fits in with everything else.

This eventually leads to one of the best sequences in recent film history: the creation and evolution of the universe. Revealing an incredible ambition and sweep that rivals Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Malick’s sequence takes us from the Big Bang and the formation of nebulae and galaxies to the beginnings of the earth, where primordial ooze eventually births life into the planet’s oceans before it finally makes its way onto the land in the imposing form of the dinosaur. Yes, we get to watch dinosaurs, particularly one troodon that makes a curious decision that reveals a fascinating mental awareness, suggesting that they too could have dominated like humans if a certain asteroid did not rain on their parade. It is a dazzling spectacle, and the fact that it takes its viewer by surprise (as any big bang should), where no indication of such an extensive meditation on the genesis of the universe is even hinted at previously in the film (There was a lot of confused mumbling during the screening I attended during this sequence.), makes it all the more potent and extraordinary. Life, as well as death, just seems to happen, and you have to go with it. And, in turn, creation itself becomes an act of self-reflection.

But the creation sequence would be far less impactful without the formation of Jack’s family and life in Waco, Texas in the 1950s alongside it. The juxtaposition between the creation of the cosmos and the formative years of the family is a marvel because its mirroring and interplay produce a keen sense of how infinitesimal human life really is in the universe while simultaneous celebrating humanity’s vitality and beauty within the evolutionary chain. Against the odds, the presentation of Jack’s first few years goes toe-to-toe with the Big Bang; with one burst of life giving way to and feeding off the other, the combination is awesome and life-affirming. From initial sights of the bottom of a newborn’s feet to the first peek at the wrinkles on an old man’s face, human life is allotted so much wonder and intricacy that the Big Bang ends up seeming like a good opening act to the human drama of the family.

This family life, seen predominately through the eyes of an adolescent Jack (played by first-time actor Hunter McCracken with great poise), lies at the heart of the film, where he and his two younger brothers are caught in between two clashing philosophies: grace, personified by their angelic mother (a fantastic Jessica Chastain) who takes comfort in the powers of love and forgiveness, and nature, brought to life by their difficult yet well-intentioned father (Brad Pitt, in one of the best performances of his career) who tries desperately to get ahead through determination and rigorous structuring. This struggle–compounded by Jack’s sexual, intellectual, and spiritual questioning/awakening–sets the groundwork for Jack’s first steps in the evolution of the man he grows up to become; it is the beginning of the road to world-weariness. And, by examining his memories and conceptions of what drives the universe (God? Nature? Nothing?), he strives to find some semblance of significance and peacefulness in his life, some solution to the warring feelings inside himself.

It’s all a lot to take in, mentally and emotionally, but so is life when you think about it, isn’t it? Which may be the film’s greatest triumph: its ability to mimic life’s tensions so astutely is what binds it, making it an indelible work of art. It may be elusive and even impenetrable at times, but the building blocks for greatness are all present, waiting to be assembled and engaged. Like adult Jack, we viewers become architects of what is shown: starting with just a free-standing door, we go through and connect the dots and work out the blueprint in the open space beyond, making what we can with what lies there. Though its ultimate construction may be unlike any film ever made, it nevertheless comes together in a way that is loose and formed–welcoming and universal to everyone. And, as encapsulated in one of its last shots, the film as a whole, with a changed perception, becomes like Jack’s high-rise, newly angled and serene in the world, within and of nature–no longer a blot, it reflects the sky’s color and clouds, becoming a gorgeous part of it. And if we were to imagine that new perspective from an eye in the sky, the construct would duly reflect us and our place in the universe, as well–a small but great component in the scheme of things because we are well aware that we are indeed a component in the greater scheme.

Easily the year’s best and most ambitious film, The Tree of Life is pure Malick–so pure that it should strike a knowing cord with anyone who literally has a brain.